Webmaster’s Note: This is a full-text copy of Freddie’s 22nd blog for the Huffington Post, which appeared there on 4 May 2012. (Feel free to leave a comment here. There is also a link to the HuffPost original at the bottom of this version, in case you wish to leave a comment there.)

Webmaster’s Note: This is a full-text copy of Freddie’s 22nd blog for the Huffington Post, which appeared there on 4 May 2012. (Feel free to leave a comment here. There is also a link to the HuffPost original at the bottom of this version, in case you wish to leave a comment there.)

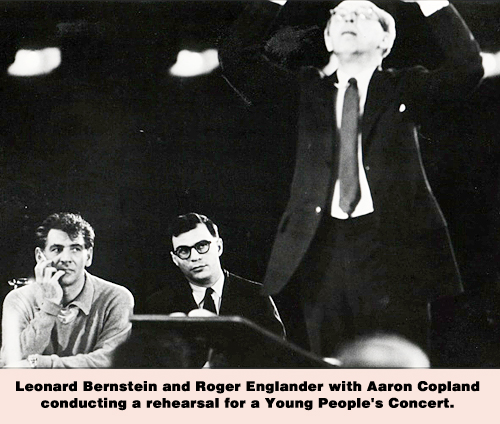

In the late 1950’s, William S. Paley (who was founder and CEO of CBS) wanted to broadcast Young People’s Concerts with America’s “glam” emerging star, conductor/composer Leonard Bernstein. Columbia Records (a division of CBS) recorded Maestro Bernstein as well as the New York Philharmonic. Maestro Bernstein, along with his buddy, Roger Englander (they had known each other for over a decade) were juxtaposed on the project. Roger and Lenny met originally at Tanglewood and studied with Serge Koussevitzky. Roger (a highly trained musician) was self-effacing and fascinated with traditional music from theatre, opera and the serious classics. He was also intrigued by new media and new forms of technology and their potential impact on communication and media. Lenny was fascinated by all things as well as being flamboyant, theatrical, photogenic, oozing star power and charm. Their collaboration became historic.

In the late 1950’s, William S. Paley (who was founder and CEO of CBS) wanted to broadcast Young People’s Concerts with America’s “glam” emerging star, conductor/composer Leonard Bernstein. Columbia Records (a division of CBS) recorded Maestro Bernstein as well as the New York Philharmonic. Maestro Bernstein, along with his buddy, Roger Englander (they had known each other for over a decade) were juxtaposed on the project. Roger and Lenny met originally at Tanglewood and studied with Serge Koussevitzky. Roger (a highly trained musician) was self-effacing and fascinated with traditional music from theatre, opera and the serious classics. He was also intrigued by new media and new forms of technology and their potential impact on communication and media. Lenny was fascinated by all things as well as being flamboyant, theatrical, photogenic, oozing star power and charm. Their collaboration became historic.

There had already been Young People’s Concerts with assistant conductors conducting them, but television was rapidly changing the world. Bill Paley wanted the Young People’s Concerts to be televised on CBS’s network from the great Carnegie Hall.

Charlie Dubin was named director and Englander producer. Englander’s right arm was Mary Rodgers, an imaginative, gifted woman and writer of children’s stories raised in a house of music as the daughter of Richard Rodgers.

The briefing format from CBS was: “Here’s Carnegie Hall. Here’s the Philharmonic. Here’s Lenny. Let him talk and conduct. Go make a show.”

Lenny created the format. Roger collaborated. Lenny loved being a teacher. His premise was: “Tell them what you’re going to do. Go do it. After you do it, explain it.”

No script writers were hired. Lenny wrote it. A bright team of production whiz-kids gave feed-back and suggestions. Lenny spoke to the audience (both live and at home) as though extemporaneously.

Roger’s job as a musician and as a producer interacting with Lenny was to make it a visual experience which would not be boring, trying to make the audience comfortable and familiar with this new experience. At the same time, he and the team had to teach cameramen the physical layout of an orchestra; how to call shots: “Camera 1, get the horns, dissolve, count of three, go to the strings, he’s getting ready to point baton to the timpani, 3-2-1… now!…” all new experiences and techniques that cameramen never had before for a fast-moving, live television experience to work within Carnegie Hall and also resonate in homes across America.

Politics intervened. Director Charles Dubin was blacklisted. Roger Englander became director of the show and thereafter for 15 years, he directed and produced it.

Being a producer/director is a monumental responsibility.

Englander read each score. He says he would then try to think of how a choreographer would meld with the conductor and the instruments and choreograph the camerawork and the musical experiences as though he were blocking actors on the stage. He listened to prior recordings of the music over and over again and then discussed everything with Bernstein as a two-man collaboration. Then, again with the team. Once Bernstein felt comfortable and was satisfied and Roger and he were in synch, it allowed him to trust the television aspects of the show to Roger while he did magic with his baton, his personality, his intellect and his musicianship.

The same crew had to be used regularly even though the shows were months apart because only they had the special experience, understanding and knowledge which came from their prior education. Cameramen had to be taught what the instruments in the orchestra looked like, viz.: differences between the violin and viola, the flute and piccolo, the oboe and bassoon, etc.

The concerts became popular.

Ultimately, global events.

They changed the world. It changed the way new technology (television) embraced and amplified the popularity of serious music and opened the television community’s eyes to new possibilities for the future.

Because the shows were so good, because Lenny was so bombastically charismatic, because Lenny and Roger worked so intimately and collaboratively – exchanging ideas and anticipating each others’ moves and needs – a television style was invented that never had before existed.

Bothering Roger, as they prepared, lurked a fallacy in the entire premise.

Concertgoers sitting in the auditorium may only see the back of the conductor waving his hands, keeping rhythm and pulling dynamics out of the orchestra. Not necessarily visually exciting from the seats of an audience’s P.O.V.

Cameras were set up in different locations on different levels of Carnegie Hall.

However, absent was the ability of the audience to see what Roger knew was the most exciting visual aspect seen only by members of the orchestra who were driven and led by this young, maniacally energetic, passionate conductor dancing and jumping as he conducted. Lenny’s body and facial expressions were a show all to themselves as well as highly effective in galvanizing the orchestra and infusing them with an adrenaline rush to keep up with his demands from the podium.

Roger said: “I didn’t want this show to be sterile. By the time an audience sees it at home, it’s in a little box with a little screen and little speakers in black and white. I don’t want the viewers’ eyes to leave the screen or their ears to stop listening. I don’t want them to leave the room.”

His solution: A peep hole large enough to accommodate a TV camera of the day!

On May 7, 2012, at Carnegie Hall a brass plaque will be dedicated – In Honor Of Roger Englander whose visionary “peep hole” (created in 1960) opened the eyes of children and music lovers worldwide to the magic behind the music – a simple hole which allowed for a bulky, cumbersome camera to look through and reveal an entire orchestra and the musical showman directing it and integrating himself with the orchestra and the music, as one. Behind the orchestra and conductor, the audience sees tiers of seats and the elegance of Carnegie Hall filled with young people and parents, all of them mesmerized. Balance that with perfectly paced live intercutting close-ups of instruments responding to motions by the conductor, different angles and points of view that different audience groups could see and how they would see from the side, the center, from above or from behind was all a new style, a new flavor, a new way to make serious music, education and teaching exciting, more exciting and dynamic for the audience at home than anything they had ever seen. It was a cinematic intimacy and revelation precipitated by imagination and creativity.

Roger won four Emmy’s for the Young People’s Concerts. He and Lenny sustained a great relationship.

The “peep hole”* has now become common, if not de rigueur in concert halls throughout the world and all the result of the inventively astute Roger Englander and his remarkable collaboration with a stimulating and exciting conductor who had enough pizzazz to drive sounds out of the Philharmonic and keep kids discovering music and an audience at home watching in a way that made them feel they were immersed in that world.

I’m so proud of Roger.

I’m so proud that he’s our friend. I congratulate him as one of the unsung heroes who helps make the world a better place.

* The Roger Englander “peep hole” and plaque was initiated by a grant from Myrna and Freddie Gershon.

Click here to see the blog at the Huffington Post site.